After a three-month stay at the great monastery the two missionaries were ready for to undertake the final long journey to Lhasa. They headed south and for a while traveled with a huge caravan which consisted of 15000 yaks, 1,200 horses, the same number of camels and 2000 men. On the 29th of January 1846, after a grueling 18 months on the road the weary but elated missionaries finally arrived at their goal — Lhasa. The golden spires of the Potala Palace, the richness of the Jokung Cathedral and the color of the pilgrims and merchants from every part of Central Asia were all overwhelming. But they had not come to sight-see and as soon as they found accommodation they began planning to conquer for Christ this citadel of paganism. When the authorities knew their presence they received an order to appear before the Regent, ruler of Tibet until the young Dalai Lama came of age. Full of trepidation and hope they obeyed. The Regent happened to be an urbane and deeply religious man and as soon as he was satisfied that the strangers were not spies but genuine men of religion, he became friendly towards them. When he asked why they were in his realm they told him that they had come to convert the Tibetans the one true religion. Far from being perturbed or angry, the Regent was delighted. Hue recorded his words; "All your long journeys were made for a religious purpose. You are right, for man’s business in life is religion. I see that you French and we Tibetans are one in this. But your religion and ours are not the same so it is important to find out which one is true. We shall therefore examine them both carefully and sincerely. If yours is true, we shall adopt it. Indeed, how could we not? But if ours is found to be true, I hope you will be reasonable enough to adopt it yourself". The missionaries could hardly have wished for a more positive reception. It seemed that all their prayers had been answered.

In the following month the three men met often, had long discussions and gradually developed a genuine respect for each other. The Regent arranged for them to learn more Tibetan so they could more clearly explain their beliefs, found them more comfortable accommodation and purchased their horses at a very generous price thus giving them much needed extra cash. As at Kumbum, curious and interested people began visiting them, some of them on a regular basis, to find out about the new religion. But just when it looked like all the missionary’s prayers had been answered, disaster struck. The Chinese ambassador had been trying for some time to have the missionaries expelled but the Regent had put him off, found excuses to do nothing or used delaying tactics. Now Chinese pressure became intense and the Regent and his government finally had to give in. After a friendly farewell from the Regent and an invitation to come again at a better time, the two men left the Forbidden City and headed east towards China.

Huc and Gabet arrived in Macao in October 1846 full of plans to establish a mission in Lhasa but their dreams were soon to be dashed. They learned that the Vatican had granted the Society des Missions Etrangeres the exclusive right to preach the Gospel in Tibet and they were not prepared to let Lazerists or any other Order poach on what they now considered to be their turf. As it happens, the Society des Missions Etrangeres was never able to get around to organizing a Tibetan mission and indeed no Catholic or even Protestant missionaries were ever to step foot in Lhasa again. Thus ironically it was not Buddhist resistance but ecclesiastical rivalry and polities within the Catholic Church which prevented the Gospel being preached in the fabled Forbidden City. Father Gabet went to Rome to plead to be able to return to Tibet but was unable to reverse the decision. He was eventually posted to Brazil where the friendship he had cultivated with Tibet’s regent, the language skills he had learned in China and Tibet and his knowledge of the region were all wasted. He died of yellow fever in 1853. Father Huc remained in Macao for two years writing an account of the mission. In 1852 he returned to France but never really recovered from the hardships of his long journey and he died in 1860 worn out at the age of 47.

This three-volume travelogue attracted much attention in academic circles, being the only first-hand acco unt of Lhasa to appear during the whole of the 19th century. It went through several editions and was translated into English. Huc’s account of the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in particular created much interest. The idea of such a tree sounded so improbable and yet in all other matters Huc seemed to be a careful and objective informant. Further, as a Catholic missionary hostile to all aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, he had no reason to say anything positive about it. Unfortunately, the truth about the wonderful tree can now never be known for certain. The British traveler Peter Flemming saw it in 1935 but it was autumn and it had shed its leaves. Andre Migot saw it in 1946 but by then it had been enclosed in a temple and he was unable to examine it carefully. Communist Red Guards destroyed the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in the 1960’s.

unt of Lhasa to appear during the whole of the 19th century. It went through several editions and was translated into English. Huc’s account of the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in particular created much interest. The idea of such a tree sounded so improbable and yet in all other matters Huc seemed to be a careful and objective informant. Further, as a Catholic missionary hostile to all aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, he had no reason to say anything positive about it. Unfortunately, the truth about the wonderful tree can now never be known for certain. The British traveler Peter Flemming saw it in 1935 but it was autumn and it had shed its leaves. Andre Migot saw it in 1946 but by then it had been enclosed in a temple and he was unable to examine it carefully. Communist Red Guards destroyed the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in the 1960’s.

unt of Lhasa to appear during the whole of the 19th century. It went through several editions and was translated into English. Huc’s account of the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in particular created much interest. The idea of such a tree sounded so improbable and yet in all other matters Huc seemed to be a careful and objective informant. Further, as a Catholic missionary hostile to all aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, he had no reason to say anything positive about it. Unfortunately, the truth about the wonderful tree can now never be known for certain. The British traveler Peter Flemming saw it in 1935 but it was autumn and it had shed its leaves. Andre Migot saw it in 1946 but by then it had been enclosed in a temple and he was unable to examine it carefully. Communist Red Guards destroyed the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in the 1960’s.

unt of Lhasa to appear during the whole of the 19th century. It went through several editions and was translated into English. Huc’s account of the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in particular created much interest. The idea of such a tree sounded so improbable and yet in all other matters Huc seemed to be a careful and objective informant. Further, as a Catholic missionary hostile to all aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, he had no reason to say anything positive about it. Unfortunately, the truth about the wonderful tree can now never be known for certain. The British traveler Peter Flemming saw it in 1935 but it was autumn and it had shed its leaves. Andre Migot saw it in 1946 but by then it had been enclosed in a temple and he was unable to examine it carefully. Communist Red Guards destroyed the Tree of Ten Thousand Images in the 1960’s.

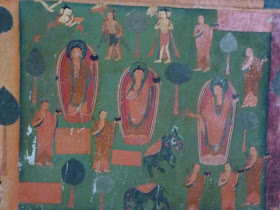

A few years ago a UNESCO-Norwegian group that came to inspect the government’s restorations at Shalu reported that ‘concrete has been used to fill a number of cracks. New paint and varnish is seen in many chapels. In the top-most Vajradhara chapel, a panel with garish new paintings does not match in any way the superb quality of the 15th originals’. In short, the so-called restorations are inept, unprofessional and destructive to the temple’s original character. We saw evidence of this too. The paintings were done in 1304 by Newari or perhaps even Indian artists and are a rare and precious survivor of this genera of painting. Those that survive are breathtaking – Buddhas, bodhisattvas and scenes from the life of the Buddha.

A few years ago a UNESCO-Norwegian group that came to inspect the government’s restorations at Shalu reported that ‘concrete has been used to fill a number of cracks. New paint and varnish is seen in many chapels. In the top-most Vajradhara chapel, a panel with garish new paintings does not match in any way the superb quality of the 15th originals’. In short, the so-called restorations are inept, unprofessional and destructive to the temple’s original character. We saw evidence of this too. The paintings were done in 1304 by Newari or perhaps even Indian artists and are a rare and precious survivor of this genera of painting. Those that survive are breathtaking – Buddhas, bodhisattvas and scenes from the life of the Buddha.

The abbot showed me where Chinese vandals have hacked a long scar down one side of a painted image with the intention of removing a whole section of wall (see picture below). In other places the eyes of all the figures have been hacked out.

The abbot showed me where Chinese vandals have hacked a long scar down one side of a painted image with the intention of removing a whole section of wall (see picture below). In other places the eyes of all the figures have been hacked out.  It seems that two principles have guided the Chinese government’s attitude to Tibetan cultural treasures – (1) Destroy the original then build a copy, and (2) Don’t trust the ‘natives’ to look after the treasures they devotedly preserved for 1500 years. Shalu offers a good example of this second principle. The circumambulatory passage around the main shrine is covered with the most exquisite paintings. Pilgrims and devotees have been shuffling through this passage since the seven centuries and there is not a mark, not a scratch, not a dirty fingerprint on the paintings. They are immaculate. And yet the Chinese have now nailed chicken wire to the lower level of these paintings ‘to protect them from damage’.Narthang is in an even worse state than Shalu. All the original buildings erected in 1033 and the famous ‘forest of stupas’ have been raised, piles of rubble being the only witness to what was once there. One of there stupas has been rebuilt in a rather poor copy of its original (an example of the first of the two principles). Only a few 17th or 18th century buildings are left standing.

It seems that two principles have guided the Chinese government’s attitude to Tibetan cultural treasures – (1) Destroy the original then build a copy, and (2) Don’t trust the ‘natives’ to look after the treasures they devotedly preserved for 1500 years. Shalu offers a good example of this second principle. The circumambulatory passage around the main shrine is covered with the most exquisite paintings. Pilgrims and devotees have been shuffling through this passage since the seven centuries and there is not a mark, not a scratch, not a dirty fingerprint on the paintings. They are immaculate. And yet the Chinese have now nailed chicken wire to the lower level of these paintings ‘to protect them from damage’.Narthang is in an even worse state than Shalu. All the original buildings erected in 1033 and the famous ‘forest of stupas’ have been raised, piles of rubble being the only witness to what was once there. One of there stupas has been rebuilt in a rather poor copy of its original (an example of the first of the two principles). Only a few 17th or 18th century buildings are left standing.

At first we couldn’t find anyone to open the doors but eventually an old monk appeared and I asked him about the library. As I half expected, he said it didn’t exist any longer but he offered to show me the old printing press. The Nathang edition of the Tibetan Tipitaka was one of four such editions and was published in the 15th century. Thousands of printing blocks lined wooden racks around the walls. I was relieved that this precious resource had not been damaged and mentioned this to the old monk. He pointed to some of the lower racks and I realized my optimism was misplaced. There were printing blocks with all the letters planed off, some were split into two, three or four, probably to be used as kindling, others were hacked in half. I found a trowel made of a cut-up printing block and an intricately carved book cover (I would have said about 14th century) split into three, again probably to make kindling.

At first we couldn’t find anyone to open the doors but eventually an old monk appeared and I asked him about the library. As I half expected, he said it didn’t exist any longer but he offered to show me the old printing press. The Nathang edition of the Tibetan Tipitaka was one of four such editions and was published in the 15th century. Thousands of printing blocks lined wooden racks around the walls. I was relieved that this precious resource had not been damaged and mentioned this to the old monk. He pointed to some of the lower racks and I realized my optimism was misplaced. There were printing blocks with all the letters planed off, some were split into two, three or four, probably to be used as kindling, others were hacked in half. I found a trowel made of a cut-up printing block and an intricately carved book cover (I would have said about 14th century) split into three, again probably to make kindling. The Red Guards had given most of the printing blocks to the villagers to use as lumber or fire wood and had used the rest for various purposes. The villagers had hidden the blocks until the glorious Communist Party of China ‘corrected’ its policy on nationalities, and then reverently returned them to the monastery. Nathang is now yet another ‘State Designated Cultural Relic’ which doesn’t mean very much after the state that’s now doing all the ‘designating’ destroyed just about all the ‘cultural relics’.

The Red Guards had given most of the printing blocks to the villagers to use as lumber or fire wood and had used the rest for various purposes. The villagers had hidden the blocks until the glorious Communist Party of China ‘corrected’ its policy on nationalities, and then reverently returned them to the monastery. Nathang is now yet another ‘State Designated Cultural Relic’ which doesn’t mean very much after the state that’s now doing all the ‘designating’ destroyed just about all the ‘cultural relics’.

The only evidence of its belated ‘State Designated Cultural Relic’ status is a few $1.99 plastic lamps illuminating the empty interior.

The only evidence of its belated ‘State Designated Cultural Relic’ status is a few $1.99 plastic lamps illuminating the empty interior.  Walking around the outside I found this fragment of an ancient sutra in a garbage heap.

Walking around the outside I found this fragment of an ancient sutra in a garbage heap.

A few kilometers before Dirapuk Gompa it started to snow, first lightly but then quite heavily, although at least it was blowing from behind us. By the time we got to the monastery, our rest for the night, I at least, was freezing cold and utterly exhausted. The thought of the next day’s march, the most arduous of the parikarma, was starting to fill me with foreboding. After several cups of tea and a cup of instant noodles I went to bed and fell asleep almost immediately. When we awoke the next morning we found that it had been snowing all night. An icy wind was blowing, the yaks were covered with snow and visibility was reduced to a few hundred yards. The view for Mt. Kailash from Dirapuk Gompa is the mast spectacular on the whole of the parikarma but we could see nothing, not even the cliffs behind the monastery or on the other side of the valley. Our whole visual world was white. During breakfast (two cups of butter tea and a boiled egg) we discussed with our guide and other pilgrims the possibilities of continuing. If it stopped snowing soon it would probably be possible to keep going, even more grueling than it would be otherwise, but still possible. If we continued and it kept snowing we could be snowed under or even end up in serious trouble. We agreed that we had to turn back. With the wind and snow blowing in our faces, the plummeting temperature and all our energy sapped by the previous day’s march, the return journey strained my physical endurance almost to breaking point. By the time we reached Chorten Kanayi I was finished. The physical exhaustion was compounded by disappointment of not having been able to complete the parikarma.

A few kilometers before Dirapuk Gompa it started to snow, first lightly but then quite heavily, although at least it was blowing from behind us. By the time we got to the monastery, our rest for the night, I at least, was freezing cold and utterly exhausted. The thought of the next day’s march, the most arduous of the parikarma, was starting to fill me with foreboding. After several cups of tea and a cup of instant noodles I went to bed and fell asleep almost immediately. When we awoke the next morning we found that it had been snowing all night. An icy wind was blowing, the yaks were covered with snow and visibility was reduced to a few hundred yards. The view for Mt. Kailash from Dirapuk Gompa is the mast spectacular on the whole of the parikarma but we could see nothing, not even the cliffs behind the monastery or on the other side of the valley. Our whole visual world was white. During breakfast (two cups of butter tea and a boiled egg) we discussed with our guide and other pilgrims the possibilities of continuing. If it stopped snowing soon it would probably be possible to keep going, even more grueling than it would be otherwise, but still possible. If we continued and it kept snowing we could be snowed under or even end up in serious trouble. We agreed that we had to turn back. With the wind and snow blowing in our faces, the plummeting temperature and all our energy sapped by the previous day’s march, the return journey strained my physical endurance almost to breaking point. By the time we reached Chorten Kanayi I was finished. The physical exhaustion was compounded by disappointment of not having been able to complete the parikarma.

After a days rest at Darchen we left for Toling and Tsaparang with the intention of trying to do the parikarma again on out our return. When we did return the sun was bright, the sky was cloudless but because it had been snowing all the time we were away, the snow was also deep – neck deep on the path around the mountain locals said. I was not as disappointed as I thought I might be. I resigned myself to not circumambulating the sacred mountain this time. Perhaps next time.

After a days rest at Darchen we left for Toling and Tsaparang with the intention of trying to do the parikarma again on out our return. When we did return the sun was bright, the sky was cloudless but because it had been snowing all the time we were away, the snow was also deep – neck deep on the path around the mountain locals said. I was not as disappointed as I thought I might be. I resigned myself to not circumambulating the sacred mountain this time. Perhaps next time.