The Himalayas are the highest mountains in the world. They form a giant arch 2500 kilometers long, between 200 and 300 kilometers wide and define the northern boundary of the Indian sub-continent. The Jataka describe the Himalayas as ‘a vast region, five hundred

yoganas high and three thousand in breadth’ (Ja.V,415). To the ancient Indians they were ‘the thousand-peaked mountains’ or ‘the measuring rod of the world.’ The Hindus scriptures know them as Devabhumi, ‘the abode of the gods’ while the Buddha called them Pabbataraja, ‘the lord of mountains’ (S.II,137)

. The exact meaning of the name Himalaya is uncertain. It may have been formed from the words

hima and

mala meaning ‘garland of snow’ or from

hima and

alaya meaning ‘abode of snow.’ Both meanings are appropriate to these majestic mountains. Viewed from a distance in either summer or winter they give the appearance of a string of pure white blossoms and no matter how pleasantly warm it may be down in the valleys during the summer there is always snow on the horizon. Although more often associated with Hinduism, the Himalayas are often mentioned in the Buddhist scriptures and were familiar to the Buddha himself. He would have seen these great ice and rock ramparts long before he renounced the world and began his quest for truth. The spectacular 8,167 meter high sentinel of Dhaulagiri can be clearly seen from his hometown of Kapila

vatthu. Perhaps he had this particular mountain in mind when he compared the virtuous person to the dazzling sun-lit snow peaks. ‘The good shine from afar like the Himalayas.The bad are obscure like an arrow shot into the night’ (Dhp. 304). Shortly after his enlightenment the Buddha is said to have used his super-normal powers to visit Lake Anotatta which is now identified with Lake Manasarovar at the foot of Mount Kilash (Vin.I,27). Later in life he occasionally ‘sojourned in a forest hut in the Himalayan region,’ probably the thickly wooded hills of the lower Kumon or the Mahabarata Hills of Nepal (S.I,116). It is hard to know how far into the mountains the Buddha may have gone but he once mentioned ‘the rugged uneven places in the Himalayas where hunters and their prey could go and beyond it, the regions where neither man nor beast can penetrate’ (S.V,148). Some of his direct disciples, following the horary tradition of Indian ascetics, would have gone up into the mountains to find peace and solitude. In the Jataka the Buddha is attributed with asking his monks; ‘Do you wish to go a wand

ering in the Himalayas?’ (

Gacchissatha pana Himavanta carikam, Ja.V,415) The Himalayas feature prominently in early Buddhist geography. India was known to the ancient Buddhists as Jambudipa and was one of the world’s four great continents. The northern border of this land was defined by the Usiraddhaja Mountains (Vin.IV,197) and beyond that were the Himalayas, the region called sometimes Himava, Himacala or Himavata. The Jataka name numerous caves, plateaus, valleys, hermitages and rivers in the Himalayas but almost none of these can be identified today. The most famous cave was at the foot of Mount Nanda and was thus known as Nandamula Cave. Pacceka Buddhas are mentioned as living in this cave and flying from there to Benares or elsewhere in India, and back again (Ja.III,157; 190; 230; 259). In one place it describes one of these mysterious saintly beings like this; he ‘wore rag robes red as lac, dark as a rain cloud, his belt was yellow like a flash of lightening and the clay bowl hanging over his shoulder was as brown as a bumble bee. He rose into the air and after having given a talk on Dhamma he flew to the Nandamula cave in the north of the Himalayas’ (J.IV,114).

Seven of the biggest lakes were Kannamundaka, Rathakara, Sihapapata, Chaddanta, Tiyaggala, Anotatta and Kunala (are these the Seven Lakes south-east of Gangotri?) and some of the more prominent peaks

were Manipabbata, Hingulapabbata, Ajanapabbata, Sanupabbata and Phalikapabbata (Ja.V,415). Two peaks that can be identified are Kelasa, now known as Kilash (Ja.VI,490) and Nanda which is of course the 7817 meter high Nandadevi (picture on the left), the second highest peak in India (Ja.IV,216; 230; 233). Amongst the first range of hills or perhaps beyond them (ancient geography is sometimes unclear or contradictory) was Uttarakuru, Northern Kuru, from which the modern district of Kulu derives its name. Uttarakuru was seen as a sort of garden of earthly delights, a paradise of eternal sunshine and free love where healing herbs and fragrant flowers grew in abundance and all sorts of fantastic creatures lived without care or toil. According to the Atanatiya Sutta the rice that grew in Uttarakuru was self-sown, fragrant and without husks, the people traveled on the backs of beautiful maidens or comely youths, the trees always hung heavy with fruit and ‘peacocks screech, herons call and cuckoos gently warble’ (D.III,199). Somewhere in Uttarakuru Kuvera, the king of the north and the god of good fortune had his jewel-encrusted palace (D.III,201). If the modern visitor travels through Garhwal or Kumaon, at least during the spring time, he or she can easily understand how such legends developed. These regions offer some of the most beautiful prospects to be seen anywhere on earth. Beyond the Himalayas was a huge mountain called Kelasa, Seneru, Neru or more commonly Meru which was thought to be the axis of the world, the point at which the four great continents met (S.II,139; Ja.I,25; III,247). Meru corresponds with Mount Kilash near the southern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Although by no means the loftiest mountain in the region all the peaks around Kilash are much lower than it, giving it the impression of immense height and grandeur. Kilash’s nearly pyramid-shaped snowy summit marked with several black horizontal gashes give it a distinct hub-like appearance. Although fanciful in parts and completely wrong in others, the ancient Buddhist conception of India and the region to its north was relatively correct. The Himalayas are the setting for numerous Jataka stories. In many of his previous lives the Buddha renounced the world and went to live as an ascetic in the mountains or retired there towards the end of his life (e.g. Ja.I,140; 362; 371; 406; 440). He and other ascetics lived of wild fruit and grains and often made friends with the wild animals. As the winter approached they would come down to the plains to escape the cold, collect salt, vinegar and other supplies and then return four months later. The Jataka explains; ‘Now in the Himalayas, during the rainy season, when the rains are incessant, as it is impossible to dig up any bulb or root or to get any wild fruits, and the leaves begin to fall, the ascetics for the most part come d

own from the mountains and take up their abode amidst the haunts of men’ (Ja.III,37). It was probably the Bodhisattva and other ascetics before and after him who first explored the more remote mountain valleys of the Himalayas and brought back to India proper descriptions of this natural and spiritual wonderland. In the beautiful Sama Jataka the Bodhisattva is described as following the Ganges into the mountains to where the Migasammata River flows into it and then following this second river until he came to a suitable place to build himself a hermitage (Ja.VI,72). The Migasammata probably corresponds to the Alakanda River which joins the Ganges near Devaprayag. Various rulers may have also played a part in this exploration as well. The Jataka tells of a king who sent an expedition into the Himalayas guided by foresters. They tied several rafts together and sailed up the Ganges (Ja.III,371).

Buddhism came to the Himalayas very early. After the Third Council convened by King Asoka five monk led by the arahat Majjhima were sent to the Himalayan region to spread the Dhamma (Mahavamsa XII,6). Unfortunately, the records do not tell us which part of the region Majjima and his companions went although it was probably either Kashmir or the Kathmandu Valley. When the Chinese pilgrim Huien Tsiang visited Kulu and its surrounding valleys in the 7th century the area still had a significant Buddhist population. ‘The land is rich and fert

ile and the crops are duly sown and gathered. Flowers and fruit are abundant and the plants and trees afford rich vegetation. Being nestled in the midst of the Snowy Mountains there are found here many medical herbs of much value. Gold, silver and copper are found here as well as crystal and native copper. The climate is unusually cold and hail and snow often fall. The people are rustic and common in appearance and are much afflicted with goiter and tumors. They are tough and fierce by nature although they greatly regard justice and bravery. There are about twenty monasteries and a thousand or so monks. They mostly study Mahayana although a few practices the other schools. Here arahats and rishis dwell. In the middle of the country is a stupa built by King Asoka.’ In time nearly the whole of the Himalayan region became Buddhist and even today Ladhkh, Zanskar, Lahaul, Spiti, Kinnaur, Mustang, Sikkim and Bhutan remain predominately Buddhist.

The modern traveler in the Garhwal or Kumaon (now within the modern states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarancal) regions of the Himalayas will find almost no ancient traces of Buddhism in the Himalayas. T

he lovely old temple at Nala has been a Hindu temple for at least a thousand years. But the stone stupas at each of its four corners and the much worn statues of bodhisattvas within it, show that it was originally a Buddhist one. On the other side of the river at Mandi are a few caves cut out of the rock in which Buddhist monks used to live and practice. Many of Tibetans refugees have established communities and monasteries in Garhwal and Kumaon in places like Dharmasala and Manali. They have as also reclaimed and sometimes even ‘recreated’ Buddhist sacred places like Rawalsa, supposedly the birth-place of Padmasambhava.

.jpg) In Dharmasvamin’s time (13th century), the Gijjhakuta was ‘the abode for numerous carnivorous animals such as tiger, black bear and brown bear,’ and in order to frighten away the animals, pilgrims visiting the Gijjhakuta would beat drums, blow conches and carry tubes of green bamboo that would emit sparks. A Buddha statue, dating from the 6th century CE, found on the Gijjhakuta, is now housed in the Archaeological Museum at Nalanda. The Gijjhakuta is located about 5 kilometers south-east of the town of Rajgir and is a popular destination for both local tourists and Buddhist pilgrims form overseas. Because the Sadharmapundrika Sutra (Lotus Sutra) was taught on the Gijjhakuta, the place is particularly popular with Japanese and Korean pilgrims.

In Dharmasvamin’s time (13th century), the Gijjhakuta was ‘the abode for numerous carnivorous animals such as tiger, black bear and brown bear,’ and in order to frighten away the animals, pilgrims visiting the Gijjhakuta would beat drums, blow conches and carry tubes of green bamboo that would emit sparks. A Buddha statue, dating from the 6th century CE, found on the Gijjhakuta, is now housed in the Archaeological Museum at Nalanda. The Gijjhakuta is located about 5 kilometers south-east of the town of Rajgir and is a popular destination for both local tourists and Buddhist pilgrims form overseas. Because the Sadharmapundrika Sutra (Lotus Sutra) was taught on the Gijjhakuta, the place is particularly popular with Japanese and Korean pilgrims.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

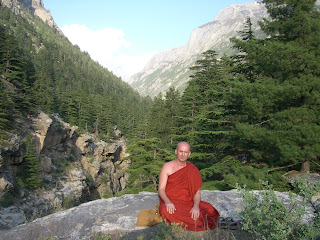

Tomorrow’s pictures will be of the Himalayas above the tree line.

Tomorrow’s pictures will be of the Himalayas above the tree line.

While the Buddha accepted that it is ligitimate for lay people to ‘indulge in and enjoy the pleasures of the senses’ (A.IV,280), he also reminded us that sense pleasures are ‘impermanent, hollow, false, deceptive, illusory, the prattle of fools’ (M.II,261). He further pointed out that sensual desire (kama raga) is a hindrance to mental calm and clarity which ‘overspreads the mind and weakens wisdom’ (A.III,63). Next, we need to think of the effect of pornography on others, as most pornography today consists of images of people. As in the case of prostitution, some of these people may work as ‘models’ because it is an easy source of income, whereas others are compelled to do it because of poverty or social deprivation. Thus, looking at such material may associate one with the exploitation of others and therefore be against the first and third Precepts. Perhaps another factor should be taken into account as well - the so-called Golden Rule. One should ask oneself; ‘How would I feel if I were to see one of my children, one of my siblings or one of my friends in a pornographic magazine of film?’

While the Buddha accepted that it is ligitimate for lay people to ‘indulge in and enjoy the pleasures of the senses’ (A.IV,280), he also reminded us that sense pleasures are ‘impermanent, hollow, false, deceptive, illusory, the prattle of fools’ (M.II,261). He further pointed out that sensual desire (kama raga) is a hindrance to mental calm and clarity which ‘overspreads the mind and weakens wisdom’ (A.III,63). Next, we need to think of the effect of pornography on others, as most pornography today consists of images of people. As in the case of prostitution, some of these people may work as ‘models’ because it is an easy source of income, whereas others are compelled to do it because of poverty or social deprivation. Thus, looking at such material may associate one with the exploitation of others and therefore be against the first and third Precepts. Perhaps another factor should be taken into account as well - the so-called Golden Rule. One should ask oneself; ‘How would I feel if I were to see one of my children, one of my siblings or one of my friends in a pornographic magazine of film?’