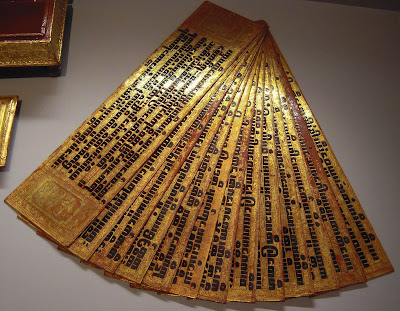

Recently I went to see the newest exhibition at the Museum

of Asian Civilizations, ‘Cities and Kings, Ancient Treasures from

Myanmar’. The exhibition is only a small

one, giving the visitor a rather hurried tour of Burmese art, mainly religious,

from the Bagan period to the 19th century. Nonetheless, most pieces are

exceptional and demonstrate the refinement of Burmese civilization. After

seeing the exhibition I had a look at some of the museum’s recent acquisitions,

including several pieces of Buddhist sculpture from Mathura, Gandhara and

China. The exhibition is on until the 5th of Match 2017

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Thursday, December 29, 2016

My 2016

This

year had not been a particularly busy one for me. It did however, mark two significant landmarks

in my life; I turned 65 in October and I celebrated 40 years of being a monk. I

made two overseas trips in the last twelve months. Together with a group of friends

I visited northern Queensland and when

they returned after a week I stayed behind for another two weeks. I spent July/August in France visiting family.

While there my brother and I visited St. Nazaire where the famous commando raid

took place during the Second World War. Over the last decade I have become

increasingly interested in the history of WWII, perhaps an unusual interest for

a monk. Our society had several prominent visitors this year. Bhante

Dhammaswami from Oxford was holed up in Singapore with a broken leg, having

fallen down in the Botanical Gardens. Bob Isaacson from Dharma Voice for

Animals in the US paid us a visit, and Ven. Anoma stayed with us for a month. My

Dhamma work received some recognition this year with the publication of Figures of Buddhist Modernity in Asia

published by the University of Hawaii Press which includes a paper about me by Meng Tat Chai. Other than this my

year has generally been quiet. Only one new book came out, A Pilgrim’s Guide to Borobudur was published in Jakarta in English

and Indonesian. I contributed an essay for the beautiful new coffee-table Sri Lanka: The Heritage of Water which

was published in Colombo just last month. I also finished my new book, A Banquet for the Buddha: Food and Drink in Early Historical India although it will not be published until

sometime next year. I decided to cut my

speaking engagements, only accepting several invitations to organizations that have been supportive of

our society over the years. Next year I plan to withdraw much more from public engagements

so I can focus on writing and meditation.

I

hope all my readers will have a happy, safe and fruitful New Year.

Thursday, December 22, 2016

Encyclopaedia Of Buddhism II

Looking at the Sri Lankan Encyclopaedia of Buddhism (SLEB) and all

the more recent ones it’s immediately clear what the problem is. They cover all

schools of Buddhism, Buddhist art, history, biographies, odd bits-and-pieces,

as well as the actual Dhamma. All religions are diverse but Buddhism particularly

so. The result is that trying to fit all this info into several volumes, let

alone in one, in encyclopaedic detail, requires that most articles have to be

kept small; in other words, they cannot be encyclopaedic. And that’s what we

see in all the recent encyclopaedias. The solution? Well, as far as the Pali

tradition goes, this is what I would like to see. There

should be an encyclopaedia which covers the Dhamma as presented in the Pali

Tipitaka, and this would require at least three or four volumes. The

translation of all Pali terms should be standardised, and where not, the reason

for it explained. Articles on doctrine should be details, comprehensive and

cross-referenced with other articles. Only a few articles should deal with the

cultural and historical aspects of Buddhism; e.g. perhaps an article each on

the history of Buddhism in Burma,

Thailand, Sri Lanka, etc. and perhaps several brief ones on the likes of

Buddhaghosa, Dhammapala, etc. The

results of trying to fit everything in can be seen in the SLEB. The article on ‘Love’ is just over six pages,

the article on ‘Metta’ just over four pages, while the article on Mahathupa (a stupa in Anarudhapura, the ancient

capital of Sri Lanka) takes up 17 pages. This sort of emphasis on Sri Lankan

history to the detriment of important aspects of Dhamma was absent in the first

several volumes SLEB but is painfully

obvious in the recent ones. Quite frankly, Thai amulet superstitions, Sri

Lankan healing rituals, Burmese nat

worship, and the like, would be more

appropriate in a book on anthropology. Another thing that should be kept to a

minimum is what might be called scholastic equivocation. Peter Harvey’s otherwise

excellent An Introduction to Buddhist

Ethics is marred by this sort of

thing. On alcohol, meat-eating, violence,

homosexuality, and numerous other issues, it’s all “The Dalai Lama says this”, “The

American meditation teacher ABC says that”, “According to the Tibetan

understanding…”, “In the Tantric tradition…” and so it proceeds so in the end

we have no idea what Buddhist ethics teach. Again we have the problem of trying to fit

everything in, and in this case, even opinions. The Dhamma as presented in the Pali Tipitaka

is pretty clear on most doctrinal and ethical issues. Where this is not the

case it is usually possible to detect historical development. For example, most

of the suttas in the Majjhima are

earlier than the Vimanavatthu and the Petavatthu and this should be

acknowledged and explained. An encyclopaedia such as this would be of enormous

help to the present and future generations of Western Buddhists trying to absorb

the essence of the Dhamma. There are now enough scholars, including several

outstanding ones in Sri Lanka, who would be capable of undertaking a project

such as this.

A

few days ago I was somewhat carried away

in a daydream (I admit to sometimes doing this). I fantasised that I had won a

lottery prize of $50 million, used the money to set up a foundation to produce

an encyclopaedia, and that the first volume had just come off the press. Then the

phone rung and I was abruptly brought back to reality. But one is allowed to

dream sometimes isn’t one?

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Encyclopaedias of Buddhism I

The Jews started their first one in 1900 and this was joined by the Encyclopaedia Talmudit in 1942. The majesterial

26 volume Encyclopaedia Judaica came out in 1972. The Catholic Encyclopaedia saw the light of day in 1907. The Encyclopaedia of Islam was first published

in 1913 and in 2005 the six volume Encyclopaedia of the Qur’an was

published. Brill’s Encyclopaedia Islamica,

a translation of the magnificent Dā'erat-ol-Ma'āref-e Bozorg-e Eslāmi, is on-going and is projected to take

up 16 volumes when finished. And of

course the recent Encyclopaedia of Islamic Law in three volumes, and the huge Encyclopaedia

of Hadith must not be forgotten. There is even an Encyclopaedia of Hadith Forgeries! The

11 volume Encyclopaedia of Hinduism has just been published. As with most things, the

Christians are ahead of the game. For reasons of space I can mention only a few of their encyclopaedias. The Encyclopaedia Biblica was published in 1899, although I think there

were several similar works before this. The Encyclopaedia of

Bible Difficulties, Baker Encyclopaedia of Christian Apologetics, The

Encyclopaedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, A Concise Encyclopaedia

of Christianity in India, The World Christian Encyclopaedia, The

Encyclopaedia of Christian Civilization, The Encyclopaedia of Christian Theology (3

vols.), The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Reformation (4 vols.), The

Oxford Encyclopaedia of South Asian Christianity (2 vols.), The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Bible and the Arts, and The Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopaedia (12

vols.). Everything you could possibly want to know about every aspect of the faith. Even a small sect like the Mormons (4 million members?)

has its

four volume Encyclopaedia of Mormonism (1992).

Now we turn to

Buddhism. In the early 1950s as the Buddhist world geared up for the Buddha

Jayanti the government of Ceylon undertook to publish an Encyclopaedia of

Buddhism, an idea that was first broached, I think, by G. P. Malalasekera.

Unusually for traditional Buddhists, a great deal of careful thought went into

the project. Specialists in Buddhism from around the world were invited to

participate and included big names such as I. B Horner, Giuseppe Tucci, B. C.

Law. P. V. Bapat, N. Dutt, Helmut von Glasenapp, and even the likes of Lama

Govinda and Christmas Humpherys. The Ceylon

government purchased at considerable expense a fine quality acid-free paper for

the volumes and made generous contributions to the project. After careful consideration it was decided

that the whole project would need 15000 pages and take 10 years to complete. In 1965 the first

volume was complete and proved to be a tour de force. But a perceptive

observer might have noticed a problem;

that of the project being

over-ambitious. It covered the doctrines of all schools, history, art,

literature, indeed just about everything related to Buddhism. It was clear that

even every book in the Tibetan Tipitaka was going to have a separate entry. How

on earth was all this going to be fitted into 15,000 pages?

Then there was the problem of being associated with the Ceylon/Sri Lankan government. Political

appointments to the editorial staff, cutback of funding, and a general slowness

started to take its toll. By volume IV (1979-1987) the project was in serious

trouble. This is reflected by the quality of the articles, although some are

still excellent, the cutback in the number of articles, the cheap paper, the

different font from the earlier volumes and the different size of each volume. Put

all the volumes on a shelf and they are all of a different size. And now the

output has slowed to a crawl. Recently I asked a former staff member when the

final volume was expected to come out; he smiled and said: “When the next

world-system starts to re-evolve.”

Of course with the

slow decline of the Sri Lankan Encyclopaedia other attempts have sprung

to life. Apart from small efforts on individual Buddhist schools (e.g. An Encyclopaedia

of Korean Buddhism and The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Zen Buddhism)

we have the new Brill’s

Encyclopaedia of Buddhism which is planned

to be in seven volumes and looks promising, the Edward Irons Encyclopaedia of

Buddhism, the Thomas Gale Encyclopaedia of Buddhism edited by Robert E. Buswell and Encyclopaedia

of Buddhism edited

by Damien Keown and Charles Prebish (only 857 pages of entries). These last three efforts cover the subjects in no more

detail than does The Princeton Dictionary

of Buddhism. As if to reinforce the perception of Buddhism being disengaged

none of them have an entry on marriage or quite a few other subjects relevant

to 99% percent of Buddhists or those wanting to know more about Buddhism.

I will say more in

this subject in my next post.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)